THE SHIPS

Ships that Americans Emigrated to Brazil on:

1. Montana – Left August 1865 W.W.W Wood of New Orleans

2. Valiant – Left April or May 1865 Rev. Ballard S. Dunn of New Orleans

3. Derby – Left January 21, 1867 from New Orleans to Galveston, TX. Left Galveston January 24, 1867 Frank McMullen. Shipwrecked at Havana, Cuba. Never reached Brazil.

4. Margaret – Left Mobile March 26, 1866 Maj. Lunsford Warren Hastings, Small pox killed 11, a few days out was forced to return.

5. Marmion – Left New Orleans in April 1867 under Brazilian Gen. Goucouris.

6. Talisman – Left New Orleans January 30, 1867 Rev. Ballard S. Dunn blown off course to the Verde Islands. Arrived 4 months later to Rio.

7. North America – Left New York April 22, 1867 Frank McMullen from the Derby crash.

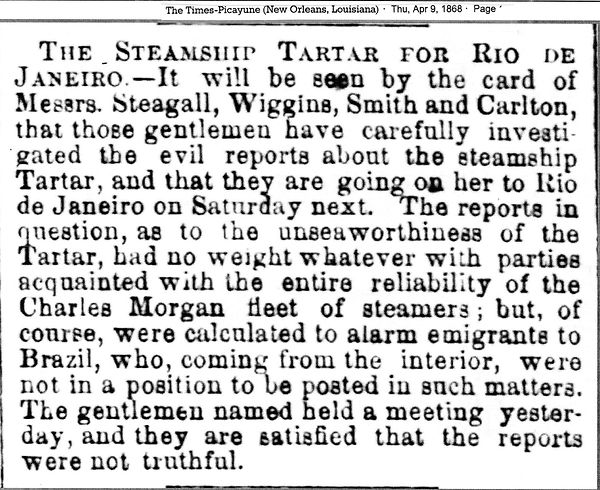

8. Tartar – Left New Orleans April 17, 1868 arrived Rio May 29, 1868. Norris, Scurlock & Mills.

9. May Queen – Left New Orleans July 1869 arrived to Brazil.

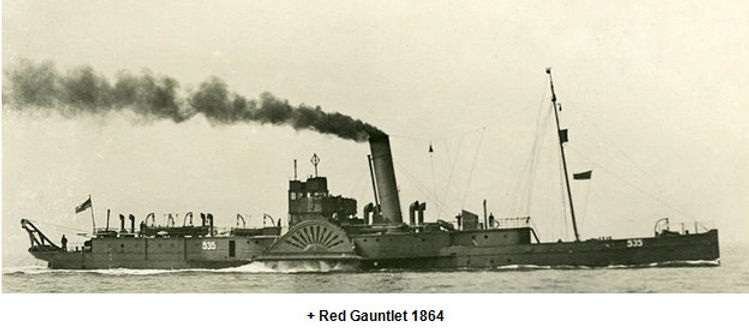

10. Red Gauntlet –Lansford Hastings ship Departing Mobile for Belem, Para, Brazil

THE SHIPS

10. The "Red Gauntlet"

The British side wheel paddle steamer Red Gauntlet was built to be a blockade runner for the Confederate Navy on January 3rd in 1865. Launched from John Scott & Sons of Greenock in the Cartsdyke Yard in April of 1864; it successfully ran the Mobile blockade from Havana under Captain Lucas, early in August that same year. The ship also served as a troop transport, only to be trapped by the Union on the Tombigbee River at Gainesville in Alabama by June of 1865. 1, 2

Somehow the vessel made it back to Mobile by June of 1866. It was sold at auction by John Hardy, the Federal Marshal, in the Federal District Court there. Notices were published in the Mobile Daily Times on Friday the 22nd of June. The Times notice also advised of the same notice being published daily in The Times and Picayune of New Orleans. 3

On December 12th, The Evansville Daily Journal [Evansville, Indiana] published a short editorial entitled: Miscellaneous, notifying the readers that - The following blockade runners were sold at Mobile by the United States Marshal: The Mary was knocked down to Col. Martin at the insignificant sum of $66,666. She cost the magnificent sum of 20,000 pounds sterling. The Red Gauntlet was bid in by Charles Cameron, of New Orleans, for the small sum of $3,200. She cost 12,000 pounds sterling. The gentlemen who purchased these fine steamers have not yet determined to what use they will convert them. They have laid in the river opposite Mobile since the close of the war, and the names of the Mary and the Red Gauntlet are familiar to every Confederate in “Dixie Land.” The Red Gauntlet was originally built for the opium trade, but failed by a few knots to meet the speed required, and was sold to the Confederate Government. 4

Hastings First Group

AN advertisement promoting passage to Brazil aboard the Red Gauntlet was published in The Mobile Daily Times, on June 20th of 1867, promoting preparations for the Southern empire [Brazil]. 5

On June 22nd J. M. Hollingsworth of 40 South Commerce Street published an advertisement in the Daily State Sentinel (Montgomery) announcing that the fast, first-class and light draught sidewheel iron steamship Red Gauntlet would sail from Mobile for Pará in Brazil on the 15th of July at 10 A.M. Passage was priced at $100.00 including freight. As booking agents would typically do, limited space was mentioned as well. 6

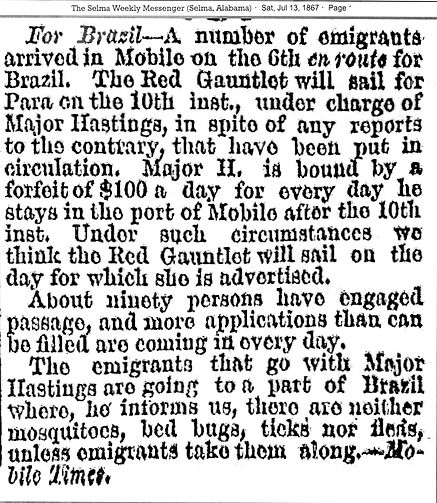

The Selma Times and Messenger also published a short notice that emigrants had arrived in Mobile on the 6th en route for Brazil. The notice declared the Red Gauntlet would sail with about ninety passengers for Pará on July 10th of 1867. It further mentioned that Hastings would be subject to forfeit of $100.00 per day if the ship did not sail as scheduled. Additionally, there was mention that more daily applications were arriving than could be accepted. [This statement was likely a promotor’s trick]. The Mobile Times was also quoted: “The emigrants that go with Major Hastings are going to a part of Brazil were, he informs us, there are neither mosquitoes, bed bugs, ticks, not fleas unless emigrants take them along.” 7

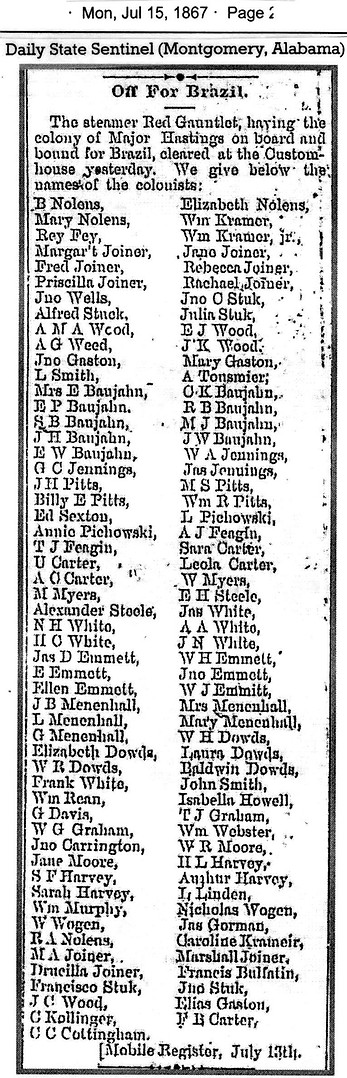

The Clarke County Democrat [Grove Hill, Alabama] published a column informing readers that the Red Gauntlet, flying English colors [Flag], under command of Major Hastings, left Mobile on the 13th with about 114 emigrants on board. The ship was in distress at about twenty miles offshore and returned to the shipyard during the evening of July 14th in 1867. Commodore Armstrong [The Naval Officer in command of the shipyard] was quoted as stating: “all facilities were afforded the steamer to repair, and that is would require but a few hours labor” adding a quotation taken from the Pensacola Observer which commented on the 16th of July that somewhat prophetically predicted the eventual plight of about half of the passengers aboard the Red Gauntlet: “She is doubtless now on her adventurous voyage, carrying from their native soil many hearts which will ere long wish to return.” 8

On the 22nd of July, the Memphis Daily Post published a very short notice: Emigrants for Brazil. To the number of one hundred and three, known as “Major Hastings Colony” sailed on the 18th from Mobile, in the steamer Red Gauntlet. However, this number does not agree with the number of passengers reported by other sources, which claimed there were one hundred-nine. It may be that the Memphis Daily Post did not include the crew while other newspapers did. 9

On September 24th, The Weekly Advertiser published a notice entitled By the Cuban Cable. It read: St. Thomas Sept. 2, via Havana, Sept. 14th – The steamer Red Gauntlet vainly seeking bottomry [a loan for repairs - with the ship for collateral], her passengers went [to Brazil] per the South America. 10

At the end of October, The Weekly Advertiser [Montgomery, Alabama] also published a column about the content from a letter written to the newspaper by Mr. R. H. Snow from Montgomery. The letter was written in September on the Island of St. Thomas, further informing the paper about the situation with the Red Gauntlet. Mr. Snow reported that the steamer was about to be sold and passengers were proceeding to their destination aboard a very similar the side wheel steamer named the South America. Their passage had been secured by the Brazilian Government.

Mr. Snow also informed the newspaper that there had been sickness aboard and three of the crew had died. The deceased were listed as: Mr. Holly, a steward who had family in Mobile; George Alan, an assistant steward, also from Mobile, and Stewart Burns who was described as a coal passer [stoker]. The Captain Charles Cameron was sick; as were two of the passengers, Messrs. Kelly and Mooney. Hastings was also mentioned as being sick, but he must have recovered because he returned to Mobile and gathered an additional group for the colony in Santarém.

Newspaper articles and notices vary in accuracy, but it appears Hasting first group departed from Mobile originally on 18th of July. There is no further information as to where or when he was actually buried. Also note: there is no record of either Mr. Kelly of Mr. Mooney arriving at the final destination in Santarém. Although, if they did not die or stay in St. Thomas. It is also possible they may have remained in Pará [Belém], or joined others who crossed paths in transit through that port on their way to Rio. 11

Friday, the 1st of November, The Montgomery Advertiser posted a short notice that the editor had learned from a letter published in the Mobilian that Major Hastings Alabama colonists had arrived in Brazil after being stranded in St. Thomas. They were in great distress because the Red Gauntlet was mechanically disabled. This notice also mentioned an un-named New York packet [mail ship] [which we know from Mr. Snow’s letter was the South America] had brought them safely to Pará [Belém]. It further mentions that Major Hastings was sick with yellow fever and could not follow them, and it concluded by erroneously reporting: Their Place of destination is “The Tocantins” in the province of Para. The Tocantins is the name of the river delta where the port city of Pará [Belém] is located. 12, 13

The Louisville, Kentucky Courier – Journal also published an identical notice on November 5th about the Hastings Colonists. 14

In 1872, additional information came to light about the fate of the Red Gauntlet (originally named the Redgauntlet*) clarifying the ship was not seized from its owner Charles Cameron by the American Consul, but rather by the British Consul in St. Thomas for failure to pay the bottomry bond that was issued in Havana by a company partially owned by the British Consul. 15

Sources:

-

Joseph McKenna, British Blockade Runners in the American Civil War, McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2019 – Page 141

-

Wise, Stephen R. – Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War, 1991 – Pps. 179 – 180, 265, 285, 317, 252, 398.

-

Mobile Daily Times, Friday - June 22nd, 1866 – Page 4

-

The Evansville Daily Journal, Wednesday – December 12th, 1866 – Page 7

-

The Mobile Daily Times, Thursday - June 20th, 1867 – Page 5

-

Daily State Sentinel, Saturday - June 22nd, 1867 – Page 4

-

The Selma Times and Messenger, Wednesday – July 10th, 1867 – Page 2

-

The Clarke County Democrat, Thursday - August 1st, 1862 – Page 2

-

Memphis Daily Post, Monday – July 22nd, 1867 - Page 1

-

The Weekly Advertiser, Tuesday – September 24th, 1867 –Page 2

-

The Montgomery Advertiser, Saturday – October 26th, 1867 – Page 3

-

The Weekly Advertiser, Tuesday – October 29th, 1867 – Page 2

-

The Montgomery Advertiser, Friday – November 1st, 1867 – Page 2

-

The Courier - Journal, Tuesday - November 5th, 1867 – Page 3

-

Hansard, Thomas Curzon - Hansards Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 209, 1872 – Pps. 346 - 347

Errata: The image of the sidewheel steamer Red Gauntlet built in 1864 was mistakenly identified as the one built 1895. The ship built in 1895 had an oil fired engine with a screw propeller, and lacked auxiliary sail masts.

* Note: Redgauntlet (1824) is a historical novel by Sir Walter Scott.

The Catherine Whiting

THE NORTH AMERICA

THE MARGARET

X

3. The "Derby"

A compilation of several first hand accounts - Most natably, Barnsley, Smith, Cook, and Gill family recollections, passengers aboard the ill-fated voyage.

A compilation of several first hand accounts - Most natably, Barnsley, Smith, Cook, andGill recollections, passengers aboard the ill-fated voyage.

The port of Galveston presented its own special problems. Washington D.C. had sent General Sheridan down to Texas to prevent Confederates from crossing the Mexican border and setting up a government-in-exile. He had done his job so well that even the French army and its Foreign Legion, there to protect Maximilion, had pulled back from the border, fearful of causing an international incident. Sheridan's legacy remained in Galveston, a city of looted stores, as anarchic and burned-out-looking as any city in the South. There, a bureau-cratic port authority was making passage out of Galveston Harbor very difficult for Confederates seeking to leave, even though the hos- tilities had ended over a year earlier, when the last Confederate warship had sur-rendered.

The Derby was scheduled to leave from the port of Galveston.

The condition of the ship was brought to attention of the Port officials; and after some repairs were made. Unfortunately, there were still several small leaks that were not adequately remedied which will play a role later on in the trip. The ever-crooked Union Port Authority in Galveston forced another payment from the emigrants before the ship was cleared to go. After cramming everything they could on the little ship, every-one finally boarded.

The ship with its 150 odd people, sailed up the coast past New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta. The first day after the Derby has left the yellow waters of the Delta, it sailed on a Southeast course. The second day out from the Crescent City, the winds became baffling and variable, and continued that way until February 8, when they became calm. The brig became virtually adrift, moving only as fast as the Gulf Stream would take it. As the ship sailed closer to Cuba, the breezes picked up and shipboard life became routine... with the passengers basking in the warm sun, or trying to learn Portuguese from Mr. McMullen.

On February 9, there was no inkling that any problems might be encountered. By mid-afternoon, the welcomed breezes turned into a high wind as a squall line bore down on the Derby from the northwest. As the norther hit, the sea quickly assumed the proportions of a tropical storm. With great difficulty, the Captain held the wheel. After dark, the fury of the storm increased. By 9 pm the yardarms were touching the water. A small leak that had been apparent since the onset of the trip worsened. Water poured from a crack, adding depth to that which had spilled below deck from the open hatches. Some of the passengers took to manning manual pumps. By 4 am one of the passengers on deck saw the rocks of Cuba no more than 1000 yards away. The Derby struck a reef. All the passengers rushed to the central salon while it was discovered that the crew was trying to lower one of only two life boat to escape. The crew quickly changed their minds when the leaders of the Texans, who had ordered them to stop, reinforced their request with drawn revolvers.

The huge waves continued to pound the ship against the rocks. She was taking on water rapidly and seemed to be sinking fast. The passengers and crew thought that all hope was lost when a gigantic wave carried the Derby pell-mell towards the rocky shore, dropping the ship as if it were a toy almost on the beach – solidly wedged between boulders. Thankfully the ship held together. Remarkably, the only injury was to Mr. C. A. Crawley, formerly of Fairfield Texas, who was thrown off of a table where he had been sleeping and broke his collarbone.

Don Juan Vermay, a wealthy brick and tile manufacturer, as well as a large plantation owner, heard of the tragedy of the Derby and moved quickly to provide assis-tance. He accommodated the large group at his hac-ienda, which was on the outskirts of Guanajay --- about fifteen mile from the wreck site --- in grand style until the situation could be stabilized.

Many of the male passen-gers stayed on the beach with the baggage and sal-vaged equipment to guard against looting by the local populace. There were a few instances of looting, with Billy Budd being in the middle of one incident.

Obviously, the wreck of the Derby necessitated a new assessment by all as to the future course of action.

Of immediate concern was the abandonment of the ship. With great difficulty, the passengers and most of the water-logged possessions were safely unloaded and taken to the beach. Although the wreck had occurred on a desolate shore with no dwellings in sight, persons who lived nearby soon appeared and spread the word to the nearby settlement of Plaza de Banes of the fate of the Derby and two other ships that had also been wrecked during the storm, one carrying 500 Chinese laborers, miraculously suffering the loss of only one life.

From family notes as related by Fleet Gill, son of Passenger Billy Budd Gill:

"One night Pa was one of the men on watch and they caught a Cuban carrying off their belongings. They knew they were supposed to turn him over to the authorities, but the man begged so piteously because under Cuban law he’d be thrown into a dungeon for 4 or 5 years. Pa and the other man guarding the pri-soner talked it over and decided to let him escape. They pretended to be asleep and the prisoner slipped away. Immediately they “Discovered” him to be missing, so the other guard pretended to shoot at him so he would run faster. They found the prisoner dead, where one shot had accidentally reached him. Soldiers came and investigated, trying to find out who actually killed him. But no one except Pa knew for sure that they hadn’t. Pa hadn’t fired his gun, so he hid in the ship until the soldiers were gone so he wouldn’t have to swear a lie about the incident."

In another case or perhaps the same one in a different version: Cubans had begun to gather near the ship and some had started carrying away belongings that had floated away from the raft. As the colonists watched, one of the Cubans came up to the side of the ship, grabbed an armload of goods, and scampered away. Jess Wright leaned over the side and pumped three bullets into the man at a distance of sixty feet. The rest of the crowd on the shore scattered at the crack of the gun. Wright's hasty action was not well-received by the Cuban authorities, and had it not been for the intercession of Confederates in Cuba, who had made friends with government officials there, Wright would probably have been marched against a firing squad wall.

It was now up to Mr. McMullan to try to resolve this very unfortunate situation. On February 22, he arrived at the Brazilian Embassy in Havana. He eventually found his way to New York on February 18th. He had vir-tually no money and had been advanced some funds from acquaintances. What money he did have was lost in the ship wreck.

After much discussion, the Brazilian Consul in New York agreed to provide assistance to the stranded group.

While all the negotiations and arrangements were being made in New York, the colonists were still being treated By Juan Vermay, described by the col- onists as “The noblest of men”. He personally went to Havana to raise money for the group of stranded emigrants.

The good news for the colonists was that about three-quarters of their supplies and baggage were salvageable……

The goup would make their way to New York from Havana aboard the "Mariposa" and continued their journey south to Brazil on the “North America”.

For the entire story see “Billy Budd – His Story”

(22 year-old Billy Budd was married to Fannie Garlington, the first cousin of the editor's great granmother. They would return to Texas a couple of years later, leaving one deceased infant buried in Brazil.)

Brigantine, two-masted sailing ship with square rigging on the foremast and fore-and-aft rigging on the mainmast. The term originated with the two-masted ships, also powered by oars, on which pirates, or sea brigands, terrorized the Mediterranean in the 16th century. In northern European waters the brigantine became purely a sailing ship. Its gaff-rigged mainsail dist-inguished it from the completely square-rigged brig, though the two terms came to be used interchangeably. For example, brigan-tines with square topsails above the gaffed mainsail were called true brigan-tines, whereas those with no square sails at all on the mainmast were called herma-phrodite brigs or brig-schooners.

The Story of the “Derby”

……Frank McMullan, leader of the “New Texas” group, had secured the English Brig Derby for $7,50.00. It was to be outfit-ted for the transport of 150 colonists. The Derby, was rated at 213 tons and did provide enough space for at least 30 families, as well as baggage and moderate amounts of farm equipment and implements. It normally carried a crew of eight to ten men and was commanded by Captain Alexander Causse. (Kass)

McMullan had gathered one hundred forty-six Tex-ans and eight Louisianians – Plantation owners and their families, and their entourage – to make the journey.

To modify the Derby for the emigrants, the settlers had had additional bunks, partitions, living accommo-dations constructed on the vessel, but even so, space and comfort were at a premium. The pas-sageway between the living quarters were so narrow that only one person could move through at a time. A hole had been cut in the forward cabin to allow air to enter the below decks sleeping quarters.

The cargo the the settlers carried with them was valued at twenty-eight thousand dollars. They took along seeds, plows, and other agricultural imple-ments, wagons, and machinery. Several cotton gins and gristmills and metal forging equipment added considerable weight to the cargo. They carried their firearms, cats and hunting dogs as well. To fit such extensive cargo and so many passengers into the ship had required careful planning. The Derby, which was twenty-eight feet wide and ninety-eight feet long, had only the interior space of a medium-sized house for cargo, crew, and 154 passengers.

Passage was paid by the group in advance with a promise that the Brazilian government would reimburse them upon arrival, as was the agreement between McMullen and the Brazilians.

The "Derby" was an out-of-date sailing ship known as a Brig or Brigantine. By the mid 1860s, ships were converting over to steam power .

Rendition of the "Derby" below

USS Guerriere

Was in use bringing immigrants back to the United States after failed colonization

Java Class Screw Sloop:

-

Laid down in 1864 at Boston Navy Yard, Charlestown, Boston, MA.

-

Hulls designed by Delano and engines by Isherwood

-

Built of unseasoned wood and with diagonal iron bracing and decayed quickly

-

Ship rigged with two funnels

-

Launched, 9 September 1865

-

Commissioned USS Guerriere, 21 May 1867, CDR. Thomas Corbin, in command

-

USS Guerriere was assigned as flagship of the South Atlantic from 1867 to 17 June 1869

-

Decommissioned, 29 July 1869, at New York Navy Yard

-

Recommissioned, 10 August 1870, at New York

-

Assigned to transported the body of the late Admiral David G. Farragut from Portsmouth, N. H. to New York in September 1870

-

Assigned to the Mediterranean Squadron in December 1870

-

Decommissioned, and laid up in ordinary, 22 March 1872, at New York Navy Yard

-

Sold 12 December 1872, at New York Navy Yard to D. Buchler of New York

-

Final Disposition, fate unknown

USS South America

THE TARTAR

THE MARMION

In Process

THE TALISMAN

The New Orleans Times, New Orleans, Louisiana, Tue. Feb. 5, 1867, page 15.

Immigration to Brazil. Mobile. February 3, 1867. -- To the Editors of The New Orleans Times, I wish to say a word to my friends and the friends of Brazilian immigration in Alabama. Having just threaded out the true route amid many counsellors and much confusion by which our people may comfortably and serenely reach their new homes in Brazil. I feel it my duty to make it known to those true souls who contemplate emigrating to that country. I have just forwarded my mother, four brothers and four sisters who, with the list appended, are all passengers from Alabama on board the schooner “Talisman”, the pioneer vessel of Dom Pedro II Line, now established under the auspices of Rev. Ballard S. Dunn between New Orleans and Rio de Janeiro. This gentleman to whom true Southerners are now as much indebted for his laborious exertions in their behalf, both in this country and Brazil, who I so thoroughly conversant with the ins and outs of the various schemes set on fact to, swindle and discourage our people in their attempts to leave the land of heart-brokenness, has so arranged this line that all who come properly recommended and couched for, can reach Brazil with facility, and under circumstances agreeable to the feelings of a Southern gentleman. To such as are ready to emigrate, I would say write to Rev. Ballard S. Dunn at New Orleans, enclosing $2.80, the price of his excellent work, entitled Brazil, The Home for Southerners, and you will get the information you desire.

He has the Sir Robert Peel, Peel a first class brig, now up for Rio de Janeiro to sail on the 1st of March; but when I left New Orleans the prospect was that her full complement of passengers would report and deposit their fare, according to Mr. Dunn's regulations, long before the time appointed. In that event, the vessel will be dispatched at once, to be followed by another, so that our people may now rely upon finding safe transit from New Orleans to Rio de Janeiro and South Brazil. I deem it worth mentioning that the Rev. Mr. Dunn is extremely careful to see that his ships are well provisioned and provided with a competent medical officer, as also with amount of coin that would enable them to repair at once without the detention of drawing - Should accident necessitate their going into any port on their outward-bound voyage. Frank J. Norris.

List of passengers for Rio de Janeiro, per schooner “Talisman”, which sailed from New Orleans on the 30th day of January.

Dr. W. C. Jones, (late of the Confederate States Navy). Thos. McCants, Mrs. M McCants, Mrs. Maggie McCants, Messrs. Robert McCants, J. R. Norris H. C. Norris, S.L. Norris, B. H. Norris, Mrs. M. Norris, Mrs. H. B Norris, Mrs. W. J. Norris, Misses Mattie Norris and Emma Norris, Mr. W .J.. Daniel. Mrs. Ann Daniel, Mrs. Mary F. Daniel, Mintie Daniel, Rosa Daniel, Messrs. Robert Daniel, Reese Daniel, Dr. G. G. Mathews, Mrs. Jane Mathews, Miss Julia Mathews, Messrs. Charlie Mathews. George Mathews, J. Whittaker, Mrs. J.P. Whittaker, Dr. E. P. Ezell, Messrs. J. D. Conyers, F. Dempsey. P. Conley.

Os Confederados: The Scurlocks to Brazil

… The next ship could have been the Talisman which was blown off course almost to Africa (Cape Verde Islands). This fits the time frame also of Leaving New Orleans Jan.30, 1867. Being blown off course could put the Ship drifting on Feb. 28, 1867. It arrived in Brazil in April......

Col. William H. Norris, a former Alabama senator was the leader of the southerners that John

and Lisanna joined for the trip to Brazil. According to Wikipedia, on 27 December 1865, (William H.)

Norris and his son Robert C. Norris arrived in Rio de Janeiro aboard the ship South America. Norris

helped establish a Confederate American presence in Americana and Santa Bárbara d'Oeste where

slavery was still legal and began cotton planting. On 10 January 1867, the rest of the Norris family

(Francis Johnson Norris and other family members and Lisanna & John Brownlow left New Orleans

aboard the Talisman bound for Rio. After a bad storm, with damage to the ship, they wound up in

the Cape Verde Islands and did not reach Rio until April 19, 1867. The Talisman was so long overdue

that the Confederates in Rio had almost given up and were thinking the ship had been lost.

On August 31, 1975, The Register printed in Danville, Virginia, printed the following

information about the Talisman voyage.

“When the voyage of the Talisman began, the ladies aboard were ordered by the ship’s captain to

remove the hoops from their skirts … the ladies stacked the steel rings on a shelf in the sleeping

quarters designated for ladies and children, and the voyage progressed under apparently normal

conditions. The passengers survived attacks of scurvy and near starvation.” After weathering a very

bad storm(s), “The ship was sailing along on a calm sea one beautiful day when land was sighted” …

“As the ship neared land, the passengers spotted palm trees.” They thought they were arriving in

Brazil, but they were in Africa. “The captain of the Talisman was completely perplexed until he

searched the ship and found the steel hoops on the shelf.” The hoops had caused a wrong heading on

the compass which had resulted in the ship being steered to the Cape Verde Islands. The hoops were

discarded and the ship set sail for and arrived in Rio.

Apparently the storm(s) damaged the Talisman so badly that it was eventually condemned:

1) The New York Herald for 23 May 1867, page 9f, reported that the schooner Talisman, Johnson,

master, arrived at Rio de Janeiro on 19 April from News Orleans, and sailed on 22 April for

Pernambuco.

2) The New York Herald for 16 July 1867, page 9f, prints the following under Disasters: that the

schooner Talisman, Johnson, master, from Rio de Janeiro for News Orleans, put into Antigua

11th ult(imate) leaking, was surveyed, condemned, and sold on the 18th at auction for (10

pounds).

Undoubtedly the ship was so badly damaged from the storm(s) that John and Lisanna and the other

passengers were fortunate that the Talisman held together long enough for them to get to Rio.

There is much information that confirms that John and Lisanna left New Orleans for Rio de

Janeiro in January 1867 and that they did arrive in Rio. There is the old family story of Lisanna going

to Brazil and that she wrote a letter back to her family describing the trip. What has been learned

about the actual trip aboard the sailing ship Talisman matches to a remarkable extent what Lisanna

said in her legendary letter. There are documents that state that John W. Brownlow was on the

Talisman when it left New Orleans. Judith McKnight Jones, a Confederado descendant, wrote about

3

the immigration and family trees. Her book, Soldado Descansa! Sao Paulo: Fraternidade Descendencia

Americana, 1998, lists some 400 families and is in Portuguese. John Brownlow is mentioned two

times in her book.

XX