RHOME

ROMULUS JOHN RHOME

MISSOURI E. ROBERTSON

RHOME FAMILY

http://hometownbyhandlebar.com/?p=3033

A Tale of Two Brothers: When in Rhome, Do as the Brazilians Do

Posted on November 10, 2017 by hometown

In our cemeteries every tombstone tells a story. And Oakwood Cemetery is a vast anthology of such stories written on pages of marble. One story in Oakwood begins with the name on a modest tombstone:

Surely Mr. and Mrs. Rhome named their baby boy “Romulus” in reference to the myth that the city of Rome was founded by the brothers Romulus and Remus, who were suckled by a she-wolf and fed by a woodpecker. (Hey, I don’t make up this stuff.) Did this local Romulus Rhome indeed have a brother named “Remus”? Did they found a city?

The answers are “no” and “sorta.”

Let’s back up to 1835 when Romulus John Rhome was born in New York to Peter and Nancy Rhome. In 1855 the family moved to Cherokee County, Texas, and in 1857 Romulus married Missouri Robertson. In 1861 Romulus enlisted in the 1st Texas Infantry in the Confederate army and served in Hood’s bri-gade. Romulus fought in the First Battle of Manassas, but his health began to fail, and he was mustered out of the army.

When the war ended, for Romulus John Rhome the South was not south enough. In 1866 Romulus Rhome, his family, and possibly some former slaves moved to Santarem, Brazil. This is Romulus Rhome’s passport application.

The Rhomes were not alone in their southern migration. After the South lost the Civil War, an estim-ated 10,000-20,000 southerners, unwilling to live under Union rule, migrated to Brazil, many of them to Santarem on the Amazon River. Many returned to the United States after Reconstruction ended, but even today in Brazil their descendants, the Confederados, are an ethnic subgroup.

In Brazil Rhome became a successful sugarcane and tobacco farmer. He also distilled rum from his sugarcane and collected archeological artifacts of local indigenous cultures. Scribner’s magazine in 1879 printed fourteen pages on Rhome’s Taperinha plantation.

Romulus Rhome’s children, such as daughter Gita, were sent back to the States only for education. His wife, Missouri, died on the plantation in 1884. Romulus died there in 1892. One account says he was shot by rebels after the overthrow of Emperor Pedro II, who had offered U.S. citizens—especially farmers—subsidies and tax breaks to immigrate.

Romulus Rhome had a brother named not “Remus” but rather . . .

Byron Crandall Rhome in 1864 married Ella Elizabeth Loftin in Cherokee County. When the Civil War began Byron, like his brother, joined the Confederate army. He enlisted in the 18th Texas Infantry in 1862 and served in General Walker’s division. Byron fought in the battles of Mansfield, Opelousas, and Pleasant Hill in Louisiana and in the Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry in Arkansas. In 1879 Byron and Ella moved to Wise County, near the settlement of Prairie Point. Prairie Point, located at the crossroads of two stagecoach routes, had been settled in the late 1850s by migrants from Missouri. By the early 1860s Prairie Point had a hotel, a school, and a post office and was the second-largest town in Wise County. But during the Civil War the area, defended only by the very young and very old, had been left vulnerable to attacks by Indians and outlaws.

By the end of the war Prairie Point was flirting with ghost town status. This Clarksville Standard article is from 1865.

But then Byron Rhome arrived in Wise County and began to breed Hereford cattle on his ranch, Hereford Park. His ranching operation was successful. And hissuccess was Prairie Point’s success. Then came more good news for the community: In 1882 Rhome convinced the Fort Worth & Denver City Rail-way to lay tracks nearby. Soon the dying town of Prairie Point was back on the map. In 1883 the rejuv-enated Prairie Point was renamed “Rhome” to honor the man who helped bring the railroad to town and whom the Star-Telegram called the “best-known breeder of pure Hereford cattle in the Southwest.”

A former ranch hand recalled that after the railroad came to town, Byron Rhome decided that his namesake town also needed a post office. But Byron could not convince the postmaster in Decatur to relocate to Rhome. So, finally, after a few drinks one night, Byron and some of his ranch hands drove a large wagon to Decatur, loaded the small post office building onto the wagon, and hauled it, lock, stock, and stamps, back to their town. The people of Decatur, of course, soon reclaimed their post office, but the town of Rhome got its own post office soon after.

B. C. Rhome was considered to be a possible gubernatorial candidate in 1892.

Byron Crandall Rhome moved to Fort Worth in 1896. He died on November 10, 1919 and is buried in Oakwood Cemetery in the Rhome family plot near Romulus John.

Ah, but the story told by the tombstone has a twist. Romulus John Rhome (1881-1926) who is buried in Oakwood Cemetery was the son of, not the brother of, Bryon Crandall Rhome. Bryon named his son after his brother.

B. C. RHOME HOUSE 1890s - Ft. Worth

JUNE 21, 1884

Rhome,

Speclal to the Gazette,

RHOME, June 20, —Mr. R. J. Rhome, brother of our worthy citizen Col. B. C. Rhome, reached our town on Wednesday. He is a resident of Santarem, province of Para, Brazil, and sailed from Para, He lives on the Amazon and brought with him many of the South American curiosities, such as the monkey and various sizes of the parrot, one of which is a curiosity, ns 1t not only talks but can actually dance. Mr. R. J. Rhome has been absent from Texas quite awhile, although he says he claims to be a Texan native to the heath. The meeting between the brothers after a lapse of sixteen years was most cordial, and from the menagerie of curiosities that he brought back, of the fruit, nut, and animal kind, we longed to be an Amazonian ourselves, if the sun does stand on his head in that tropical clime.

.jpg)

.png)

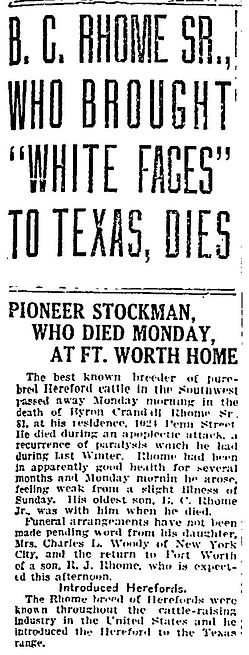

B. C. RHOME Sr., WHO BROUGHT “WHITE FACES” TO TEXIS, DIES

PIONEER STOCKMAN, WHO DIED MONDAY, AT FT. WORTH HOME

The best-known breeder of purebred Hereford cattle in the Southwest passed away Monday morning in the death of Byron Crandall Rhome Sr., 81, at his residence, 1624 Penn Street. He died during an apoplectic attack, a recurrence of paralysis, which he had during last Winter. Rhome had been in apparently good health for several months, and Monday morning he arose, feeling weak from a slight illness of Sunday. His oldest son, B. C. Rhome Jr., was with him when he died.

Funeral arrangements have not been made pending word from his daughter, Mrs. Charles L. Woody of New York City, and the return to Fort Worth, of a son, R. J, Rhome, who is expected this afternoon.

Introduced Herefords

The Rhome breed of Herefords were known throughout the cattle-raising industry in the United States and he introduced the Hereford to the Texas range.

PASSPORT PHOTO

FARM TAPERINHA

Located in the Ituqui area (80 km from Santarém), it is accessible by river. From Santarém, one navigates by the Tapajós river until the entrance of Lake Maicá, traveling all the way until arriving in Paraná Ayayá, where the farm is located.

Natural reserve and historical-scientific monument, the farm belonged to Barão de Santarém, An-tônio Pinto Guimarães, in the nineteenth century, who took as partner the American immigrant Romulus J. Rhome. Under the administration of Mr. Rhome, who came to reside there with his family, the property has progressed significantly, standing out among the existing ones in the mun-icipality. Frontier to the house was the mill, with steam-powered mills, novelty at the time. It was in Taperinha that the first steam boat was built in the Amazon region, which received the same name from the Fazenda.

Mr. Rhome devoted himself to doing archaeological research and, it is well known, was the first to be interested in this type of activity in Santarém. He collected the strange clay figures he found or ordered to be unearthed, such as buzzard heads, crested roosters and deer, stone axes, etc., and several exotically ornamented urns containing calcined human bones. The Rhome collection was incorporated into the Museum of Rio de Janeiro, through the American professor Charles Frederic Hartt who traveled the region on field trips.

In 1882, the Baron of Santarem died. The following year the society between the Baron and Mr. Rhome is undone, and the heirs of the Baron were in possession of the half of the sugar mill that belonged to Mr. Rhome, as well as the slaves of the property.

In 1917 the German scientist Godofredo Hagmann settled in the estate, where he installed and managed, along with his wife Júlia Hagmann and later, his daughter Érica, the first meteorological station in the Amazon, whose operation lasted until the decade of 70. To the main house, with large rooms, bedrooms and kitchen, Mr. Hagmann attached a library.

The sambaquis found on the site are quite extensive and are up to 6.5m thick. Associated with the deposits of sambaquis are ceramics, whose dating, carried out by the researcher Ana C. Roosevelt, of the Field Museum of Chicago, revealed ages approximately of 8,000 years, being one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the Amazon, since represents the oldest pottery ever found in the Americas.

Just as the Portuguese government decided to establish hereditary captaincies in the Northeast. There are indications that in the North region there were also sugar mills (only Taperinha will be approached) focused on large-scale production of spirits for marketing purposes with Europe. The real proof of these indications is that in Santarém Baron Miguel Pinto acquired from D. Pedro II the title of possession of a vast property of 42 km of area called Taperinha that means ruin, old house or quality of life according to the silvícolas. With an entrepreneurial vision, Mr. Romulus J. Rhome, one of the immigrants from the advent of American immigration, who had the capital to construct the plantation, became the partner.The property is managed by Graziela Hagmann, one of the heirs of the estate. In fact, knowing the place depends on the approval of the family, who lives in Santarém.

The studies of the archaeologist Anna Roosevelt attest that the city of Santarém was born in Taperinha. For Anna Roosevelt apud Funari (2006, 80), the Mongols arrived in the Lower Amazon between 8 and 11 thousand years ago by the Bering Strait and later gave birth to the main Amazon tribes such as the Tapajó (No Nhengatu is not pronounced plural with s). During the expeditions of Anna Roosevelt's property in 1986 and 1993, she launched as theory the fact that Taperinha is the oldest South American archaeological site due to having found monteiroeros of sambaquis, traces of ceramicstapajônica dating from 8 to 11 thousand years and mainly "tierra black "that characterizes the presence of the prehistoric man, since this one is fruit of the decomposition of organic residues deposited by the own hominids. However, the following questions remain in locus; What are the similarities and differences between taperinha and other engenhos? Was sugarcane production invested only in cachaça or also in molasses? What end did the slaves have? What is Taperinha's relationship with the cabanagem? What is the scenario of Taperinha's economic relationship with Europe? Nonetheless, we have noted the architectural and structural similarities between the Nordestinos and Taperinha mills, which, in the midst of variations, resembled: A mansion, a complex encompassed by an ingenuity, a chapel, a What are the similarities and differences between taperinha and other engenhos? Was sugarcane production invested only in cachaça or also in molasses? What end did the slaves have? What is Taperinha's relationship with the cabanagem? What is the scenario of Taperinha's economic relationship with Europe? Nonetheless, we have noted the architectural and structural similarities between the Nordestinos and Taperinha mills, which, in the midst of variations, resembled: A mansion, a complex encompassed by an ingenuity, a chapel, a What are the similarities and differences between taperinha and other engenhos? Was sugarcane production invested only in cachaça or also in molasses? What end did the slaves have? What is Taperinha's relationship with the cabanagem? What is the scenario of Taperinha's economic relationship with Europe? Nonetheless, we have noted the architectural and structural similarities between the Nordestinos and Taperinha mills, which, in the midst of variations, resembled: A mansion, a complex encompassed by an ingenuity, a chapel, a

The economic activity in Taperinha in the middle of the nineteenth century was linked to the exploitation of sugar cane for the purpose of producing the brandy, tobacco production for the specific use of the Barão de Santarém family, logging, cocoa plantation, the production of orange, cashew and cupuaçu wines, the cultivation of vegetables and legumes coated in the consumption of farm animals, as well as the cultivation of curauá, where their fibers were invested in the production of ropes and marketed in the region and elsewhere. In Taperinha the muscular blacks fed all day the great sugar mill. The plantations were in the upper part of the land, where they were cut by hand and taken to be thrown in the zinc channel that led them near the mill, which would later apply the broth in large-scale production of spirits and small-scale molasses. The fiery water was boxed and exported to Europe, already molasses, mainly to Amsterdam in Holland where it was refined and whitish in the so-called "Purgatory houses".

In addition to the Engenho there was a rustic sawmill where the most varied kinds of hardwood were explored, such as the Jacaranda, the Muiraquatiara, the Muirapixuna, and the rich Pau D'arco brown. As far as the Cabanagem in Santarém is concerned, the small passage accurately transcribes this movement in Santarém:

In early 1835 the situation was already bleak. The seditious were scattered in armed groups that assaulted settlements, farms, places, killing, devastating, plundering, ... Who could escape, flee, burying their possessions, jewels and valuables, hoping to recover them later, when the end of the civil war ... (SANTOS, 1999. p.197-198).

The historian, like any scientist, works with evidence and assumptions. [...] If he does not risk hypothesizing from assumptions, he risks repeating the already known, reaffirming the obvious, ... If, on the other hand, he abandons the evidence and allows himself to "delirious" at will, can create an interesting work of fiction [...], compromised only with the creative imagination of the author. From this we infer that in fact Taperinha was influenced by Cabanagem, where the Tupaiulândia section affirms that at the time of the revolt many farmers and elitist hid their wealth so as not to be plundered by the cabins, in the mill there was no difference other than in Alcova da mansion there was a hole that was supposedly used for such purposes of prevention against the rebels. There is striking evidence - at least verbal - that the Engenho served as a strategic point for interception of food and communications between the huts of the interior of the Tapajós, where the military garrison was sent to the region by the 1st judge of the Comarca de Santarém, Dr. Joaquim Rodrigues de Sousa. It can not be said exactly whether the garrison suffered defeat, but it can be inferred that it succeeded at the end of the "popular" movement, where it succeeded in repressing the rebels. It is noteworthy that in 1883, the society between Rhome and the Baron was undone, because of his death, and the planters and slaves were divided by their descendants. From this, many of Taperinha's slaves were brought and sold in Santarém, others offered the festivities of N. Sra. of Conceição,

When there is previous contact, groups, especially students, usually explore the property. The place has all the characteristics for the development of scientific tourism, but also the adventure. After a walk of several minutes you can reach a very high point, seen as a gazebo, which provides a privileged view of the entire region of Ituqui, as well as nearby lakes and even the Amazon River. With a little physical conditioning and the help of a tour guide gives you to know part of the forest. The walk can be arranged in an igarapé bath, which serves to refresh the body and prepare the trip back.

The boat is the most used means of transport to reach the place, but during the summer the access is also by car, facing, of course, the difficulties of the road of beaten ground. It is, without doubt, a must-see.

Traces of the Mill of Taperinha Engenho

THE COMPANY OF THE BARON OF SANTARÉM WITH ROMNIUS 1 RHOME AND THE FARM TAPERÍNHA

THE SOCIETY OF BARÃO DE SANTARÉM COM

ROMULUS J. RHOME AND THE TAPERINHA FARM.

Source: Taperinha: history of natural history research carried out on a farm in the region of Santa-rém, Pará, in the XIX and XX centuries / Nelson Papavero;William L. Overal, organizers - Belém: Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, 2011, p.43.44, 45.46, 47, 48, 49, 50 and 51.

National, Commander and Dignitary of the Imperial Order of the Rose [cf. Fig. 4.31; 4, 3 'and 20 (from July 31, 1855 to July 1856, May 16 to November 8, 1869, and November 5 from 1872 to 18 April 1873) Vice-President of the Province, and in 1871 he was awarded the title of Baron de Santarém ... As a politician, he always militated in the ranks of the Conservative Party, taking over the leadership from 1848 ... This illustrious vario succumbed in the dawn of August 16 of this year, the same day in which was completed 19 months after the death of her shaken consort. He leaves eight children, three of whom are still younger. "He has four reports published (Guimarães (MAP), 1855, 1869a, 1869b, 1873).

According to Meira. (1976: 7), "Having begun his life poorly, fishing to survive, and then becoming the owner of many fishing vessels, and later as owner of farms in Prainha [cf. Sánchez 1998: 226, note 541 , in Monte Alegre in Alenquer, cacauais, sugar plantations [Taperinha], rubber plantations and native and wild rubber plantations, became an absolutely rich man, to the point of leaving for the children of the wife who had Baroness, a good beginning of life, apart from the jewels of his wife who were count-less gems that touched the six legitimate daughters. "

He had a brother, Manoel Antônio Pinto Guimarães, who had died before him. In the cemetery of Santarém this is his tomb, next to the tombs of the Baron and the Baroness of Santarém [photo in 4ª. of pages of unnumbered figures, between pp. 320 and 321 of Meira's book, 1976].

Miguel Antônio Pinto Guimarães married, on January 16, 1845, with D. Maria Luíza Pereira [born on January 6, 1828] [Fig. 4.4], daughter of Pedro José de Bastos and D. Maria Francisca Pereira, orig-inally from the Vila de Viana, Freguezia do Monte, Archbishopric of Braga, Portugal, then deceased, in the Church of Our Lady of Conception, in the town of Santarém.

The famous naturalist Henry Walter Bates, who met him in 1851, on his second visit to Santarem, on which occasion he took three and a half years, thus referred to him (1863, 1944: 10): to the small crimes of his fellow citizens, but he is very respected. A nation can not be despised, whose best men can rise to positions of trust and command. "

Avé-Lallemant (1860,1980: 76) also praised the Baron, who came to know in 1859: "The arrival of the steam boat was the main event in Santarém, and everyone was looking at the Marajó. Upon landing, I was able to give the recipients the letters that would facilitate access to Santarém, one for the comp-any's agent, Mr. Joaquim Rodrigues dos Santos, another for the lieutenant colonel and commander, Miguel Antônio Pinto Guimarães, one of the men of great prestige in the province and the first in Santarém.

They would gladly have filled me with every possible kindness, but our fleeting permanence did not give me time for this. Both were very pleasing to me by the frank obsequiousness.

I was particularly interested in the old commander, Portuguese by birth [two inaccuracies: Pinto Guimarães was 50 or 51 years old at the time, but, as Bates had said, he was early gray; and he was a native of Santarém], a man who made himself and who, as I was told, had begun his career in the Tapajós, driving his own canoe, in which his personal tapuia gave himself to fishing. He had accum-ulated a fortune of 300,000 thalers, with such a simple industry which is certainly not easy. Its beginning and its end honors the old [sic], which seemed to me envied by many. "

Avé-Lalleman then devotes a few lines to the site of the future Barão de Santarém (Figs 4.5 and 4.6), currently located in the center of the city of Santarém, on the street Senador Lameira Bittencourt (former merchants' street):

"The house, on the banks of the Tapajós [sic: of Amazonas], is magnificent, with seven front windows on the ground floor, the rooms are clean and well-furnished, and in the living room you can see a vertical piano. very well arranged, and without the fagot staff in the house, it would be considered not to be in Brazil, not to mention the Tapajós. "

The three-storey house had the ground-level facilities for trade and / or the quarters of servants, slaves, and travelers, whose access to the street is through six single, wide doors, as well as a main door. The second and third floors were intended for the owner's and his family's quarters. Amorim (2000: 1581-59) gives more details of the diverse destinies that had this splendid building after the death of the Baron.

If the "mill" referred to by Bates (see above) is really the Taperinha Engenho, then we have here the minimum date (1850) in which he passed from the hands of José Joaquim Pereira do Lago, or his heirs, to the Manuel Antônio Pinto Guimarães. As for the name "Taperinha", it will only appear in literature in 1870, in the work of Hartt (see chapter 7).

After the arrival of the confederates in Santarém, Miguel Antônio Pinto Guimarães formed a partner-ship with Mr. Romulus John Rhome, for the development of Taperinha Mill. Romulus John Rhome was born on March 7, 183 in Frankfort, Herkimer, New York, the second son of Peter Gremps and Nancy Almira Crandall Rhome (whose first daughter, Elizabeth Clarinda Rhome, was also born in Frankfort, Heridmer, NY , on March 15, 1833 and died on February 28, 1920). By the year 1837 his family had settled in Richmond, Virginia, where, on November 22, 1837, his brother Byron Crandall Rhomne was born. The Rhome family, in the year 1840, was in Camak, Warren, Georgia, where their daughter Almira Georgia Rhome was born (August 3, 1840: died March 13, 1863). After the death of Mrs. Rhome, on August 25, 1840, in Camak, the family moved to Jacksonville, Cherokee County, in the Chartered, in the early 1850s.

Peter G. Rhome was very successful economically and became a large landowner and operated a mer-chant company in Jacksonville.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Peter was the representative of Cherokee County at the Secession Convention. Romulus J. Rhome enlisted in the 1st Texas Infantry in the spring of 1861 as Second Lieutenant, and served in General Lee's "Hood's Brigade." He participated in the first Battle of Man-assas. For being sick, she had to return to Texas. Byron enlisted in the 18th Texas Infantry, Company K, of Jacksonville (Cherokee County, Texas), in July, 1862. He served in the General Walker Division in the Trans Mississippi Department, spending the war years in Louisiana and in Arkansas: began his service as First Sergeant, then was elected Second Lieutenant and then promoted to First Lieute-nant. He was injured at the Battle of Opelousas but continued on active duty until the 18th was dispersed in Hempstead, Texas,

Romulus was married at an unknown date to Missouri Robertson Rhome, and the two decided to emigrate to Brazil in 1865, to settle in Santarém, Pará.

Byron Crandall Rhome married Ella Elizabeth Loftin on August 31, 1864, in Cherokee County. In 1876 he moved to Wise County, where he started to raise Hereford cattle at his ranch. His wife passed away in 1879, probably from a typhoid fever. Byron Crandall Rhome died on November 10, 1919, in Fort Worth, Tarrant, Texas.

Undoubtedly the most successful of the Confederate settlers, Romulus John Rhome dedicated himself at the Taperinha Farm to various activities. Of him said Guilhon (1979: 181-185): "At the root of the Taperinha mountain range, on the banks of the Ayayá River, the Baron de Santarém had a large settle-ment situated on a vast expanse of land that measured for square miles.With the advent of American immigration, he took him as a partner to one of the immigrants under the dynamic and efficient administration of Mr. Rhome, who came to reside there with his small family, the property knew its most flourishing days and progressed, surpassing, after some time, all other existing in the muni-cipality.

The large dwelling house was covered with tiles and frontier to it was the mill. The taperinha mills were steam powered. At that time there were several mills scattered in the region, but this type was novelty and was the most powerful of all. It moved with the waters of weir, brought by a long artificial channel [cf. Fig. 20.361. As in other American plantations, most sugarcane juice was distilled in cach-aça. Mr. Rhome soon improved the sugar evaporators by predicting that this production would become quite profitable.

Muscled blacks fed all day the great mill of letter [Cf. Fig. 9.31 and carrying the bagasse. The planta-tions were on the high ground. The cane was cut by hand and taken up in b0 car. There she was thrown into the gutter that led to the mill. This large wooden gutter descended in the shape of a half horseshoe and ended near the. mill house It was about 400 feet tall.

Beyond the mill there was a sawmill. The most splendid woods grew in the neighborhood. There was the jacaranda, the muirapixuna that looked like iron, and the rich brown duck. Of all the muiraqua-tiara stood out, striped black and yellow. All were polished exceptionally, and some were so hard and tough that they were advantageously used in place of iron and copper. In the sawmill, even the roof was set in fine hardwood, just as all the machinery was mounted on marvelous woods rich in color.

In Taperinha, besides the own products of the mill, also excellent wines of orange, cacao, cane, cashew, etc. were manufactured. The corn, the rice, the beans, the tobacco, the cassava, the cacao were also grown there. Under the direction of Mr. Rhome the plantations were developed with the aid of the plow. It was very beautiful the view of the sugar cane stretching for more than half a mile on all sides.

Everything that was consumed in Taperinha was produced there. Fish and turtles abounded in the lakes. The hunt was full and varied. The fruit was made of various kinds of wine, and to top it all, even the cigarettes were made from the fragrant Taperinha tobacco. In fact, there were about fifteen or twenty men on the estate who were exclusively engaged in the preparation of tobacco by local proces-ses [Cf. FIGS. 9.4 and 9.5].

Mr. Rhome built a bathhouse where one could swim in the cemented pool and take a shower bath with one hundred gallons per minute.

Mr. Rhome's greatest distraction was to collect the strange clay figures he encountered or ordered to be unearthed.They were easily found throughout the region. For years he was dedicated to do arch-aeological research and, it is known, was the first to be interested in this type of activity in Santa-rém. So he was able to gather buzzard heads, crested and barked roosters, stone axes, etc., and several exotically ornamented urns containing calcined human bones. For a long time, the tribe of the Tapajos had inhabited the ravines that border the river and which were intensely populated. The sophisticated pottery, however, say the experts, is more than certain to have belonged to another people, of superior culture, much older than the Tapajós and until today unknown.

The American professor Charles Frederic Hartt [see Chapter 71, who toured the region on a study tour], became deeply interested in that taperinha dish, soon recognizing the importance of the disco-very. Later, the Rhome collection was incorporated into the collection of the National Museum, through Prof. Hartt. Many years later, as a result of strong floods, in the city of Santarém, much more valuable and beautiful pieces were unearthed, resembling the Mayan and Inca ceramics: idols, vases and urns, which until today are challenging deciphering as to their origin and history of the people who produced them.

*

In 1882, the Baron of Santarem died, of whom Mr. Rhome was a partner. A few days after this fact, Mr. Rhome had the following denial published in the newspaper of Santarém, probably because of some news circulating in the small town:

"It is utterly false that there was never the slightest disagreement between my very mournful friend the venerable Mr. Barão de Santarém and the undersigned, referring to our society at Engenho Taperinha.

It is equally false and slanderous, that I have demanded the large sums from which it was proclaimed, as the balance of accounts of the social form; for which, they say, I have asked for the intervention of my consul and adjusted lawyer in the capital.

It is finally false that there were never any motives during the years of my residence in Santarém to complain to me of the lightest of any member of the illustrious family of that meritorious elder, for whom I have only expressions of grateful acknowledgment and high appreciation.

Serve, therefore, these lines of denial to the vis slanderers. "(Jornal" O Baixo Amazonas ", No. 36, 16.ix.1882).

Finally, in April 1883, the inventor of the late Baron made public by the same newspaper that he had liquidated the industrial society that the deceased had signed with Mr. Rhome at the Taperinha mill, at the rate of Pinto & Rhome, acquiring by purchase for the heirs of the Baron was the domain of half of the estate belonging to Mr. Rhome, as well as the slaves of the estate.

Missouri Robertson Rhome, wife of Romulus John Rhome, died in Santarem on February 23, 1884. The couple had only two children, Romulus John Rhome Jr. and Byron Rhome. The former was perhaps married, for there are references to 'probably daughters of one of them, in Pastor Henning-ton's diary. Romulus Jr. died tragically in a firearm accident in 1887. Mr. Rhome also died in Santarém on July 9, 1892. The following year, his son Byron went to the United States, probably for ever , since all his family in Brazil was extinct. As with others, the name Rhome disappeared from Santarem be-cause of the lack of male descendants.

Miguel Antônio Pinto Guimarães, the future Baron of Santarém (Figs 4.2 and 4.3) (Vasconcelos & Vasconc-elos, 1918; Meira, 1976) was born in Vila de Santarém (Fig. 4.11, in Pará, on June 8, 1808, with his parents Miguel Antônio Pinto Guimarães (whom we have already seen in chapter 2, receiving in sesmaria the island of Ituqui) and D. Tereza Joaquina de Jesus. Of small stature (perhaps a meter and a half, and no more), it was endowed with extraordinary energy and great work capacity. The first time he heard of his name, according to Meira (1976: 9), when he was only 23, he attended a meeting called by the military com-mander, João Batista da Silva, sergeant-general of the 4th Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Line of the Army, on September 16, 1831, to deal with the defense of Santa-rém, still a village, against the factious partisans of canon Batista Campos who had revolted. This advice was from all the official garrison authorities, merchants and farmers, who were truly threatened in their life and in their patrimony. According to his obituary, publish-ed in the newspaper Baixo Amazonas, year XI, no. 33, dated August 17, 1882 (in Meira, 1976: 11): "Miguel Antônio Pinto Guimarães [was] invested in the com-mand of the corps of workers, who was later exting-uished, and thereafter served collectively Provincial Legislative Assembly, in the legislatures of 1852 and 1868, Deputy to the General Assembly in the legislature of 1855, Colonel Commander Superior of the Guard

Figura 4.2. Miguel Antônio Pinto Guimarães, Barão de Santarém.

Figura 4.3. Miguel Antônio Pinto Guimarães, Barão de Santarém, em idade mais provecta.

Figura 4.4. A Baronesa de Santarém (Maria Luíza Pereira)

.png)

Figura 4.6. Vista do Solar do Barão de Santarém, em 1932.

%20(1)_png.jpg)

Figura 4.5. Vista do solar do Barão de Santarém (com três andares), em Santarém.

The Baron's Residence